|

Crime & Punishment Part 2

Owen Miller’s Central Hotel, which opened in 1902, and rented out pack trains for trips to the Sespe Hot Springs and Lockwood Valley. Owen Miller is below the lamp post, George Henley is in the back seat of 1907 Model N. Ford. Photos courtesy Fillmore Historical Museum. By Gazette Staff Writers — Wednesday, February 23rd, 2022

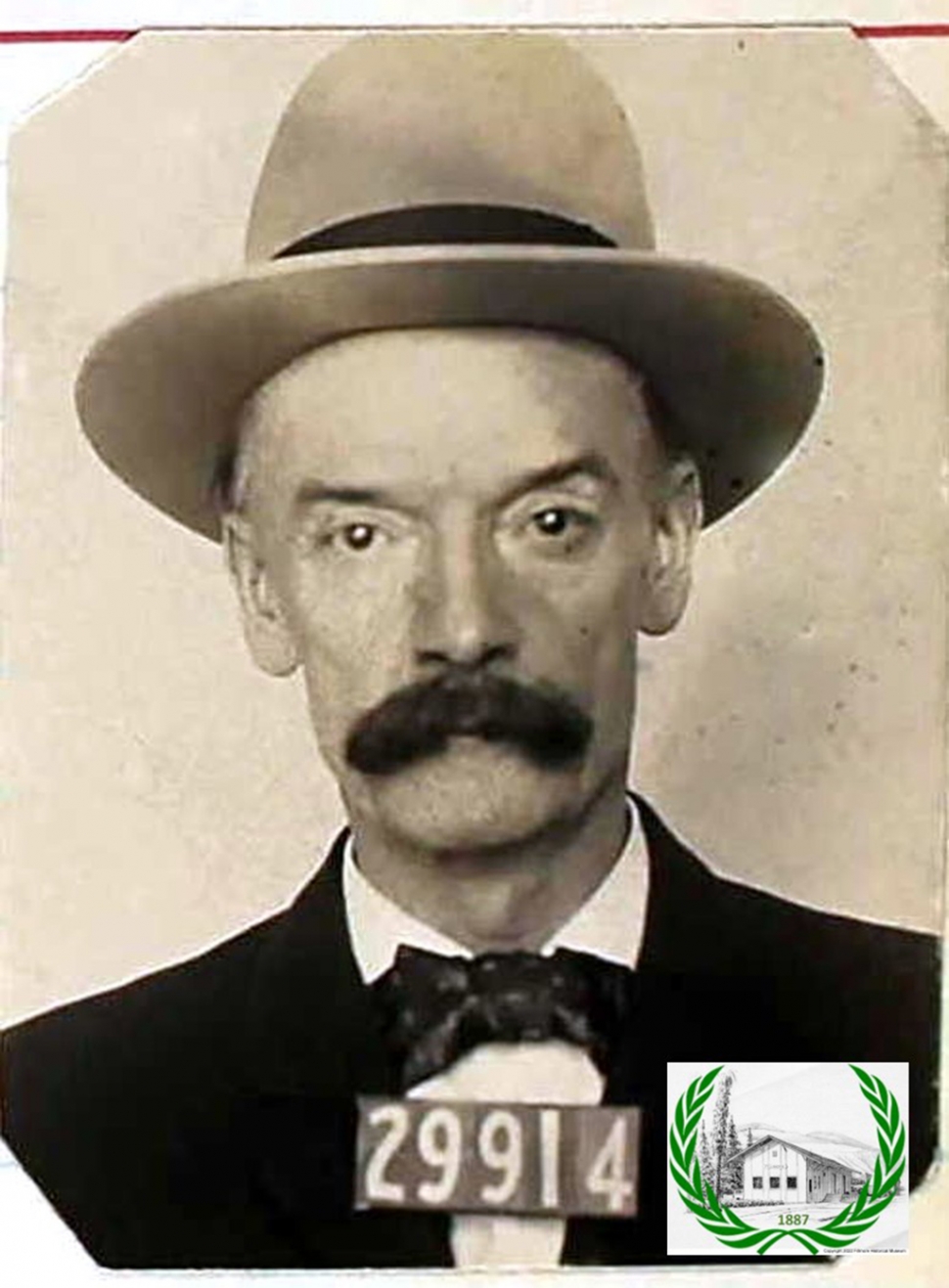

Lawrence Hinckley, who witnessed a shooting between Mason Bradfield and the George Henley.  Mason Bradfield’s San Quentin Prison Photo in 1916. Mason’s prison register 1910-1918.  Judge Merton Barnes. [Courtesy Fillmore Historical Museum - From “Old-Timers’ Tales of Fillmore” by Edith Moore Jarrett. Originally Crime and punishment were sometimes a bit mixed up as in the case of our Constable Owen Miller, said by the Ventura Free Press in 1899 to be “the best-known man in Ventura County.” He came here in 1888 by train from Pennsylvania and was raising cattle up Sespe Canyon by 1893. Around 1902 he owned the Central Hotel in town and rented out pack trains for trips to the Sespe Hot Springs and Lockwood Valley. By 1918, he was running for reelection as constable of Fillmore Township, and in 1918, his professional card in the Fillmore Herald advertised, “Private detective work of all kinds. Member National Detective Service Association.” One can hardly imagine our village needing a real live detective, but many did approve of his sideline. You see, he was said to be the town bootlegger, amused by his double role and frank about it to everybody but his boss, the county sheriff, who kept trying to catch him at it. Haskell Schell, as a teen-ager, worked for Miller in his livery stable and heard some gleeful stories of his boss’s moonshine moonlighting. Seems that Miller told him that he had arrested a couple of local fellows and had to take them by train to the Ventura jail. He didn’t handcuff them, so when the train slowed for Santa Paula, the fellows jumped out the open window and ran away. Miller just leaned out and yelled, “Hey, you! Come back here!” which, of course they didn’t. “They’d have been locked up for 90 days,” he explained to Haskell, “and they were two of my best customers.” Another time, on a similar errand, Miller told how he handcuffed a prisoner and kept a wary eye on him all the way. Why hadn’t he let him go, too? “He was my worst competitor, a bootlegger,” the constable chuckled. “It was good business to get that guy locked up for 90 days.” Once when the Ventura sheriff decided that Miller had gone to far, he planned to sneak in unexpectedly and administer a little punishment himself. But someone had tipped off Miller, who removed the bottles from his little hotel and buried them all in the manure pile behind his table. The sheriff searched the place in vain. No evidence. After he had gone, Miller went out to uncover his cache. It had been a hot day, with the sun shining on the barnyard. You know what happened. Every bottle had burst from the heat. Even Miller got a good laugh out of the story when he told it himself. [Miller had to deal with some big-time crime] in 1915 when Mason Bradfield shot George Henley in broad daylight right in front of the Orange Leaf Café. The two men had been feuding for years, both owning property up the narrow Big Sespe Canyon, for Henley was apparently uncooperative about a right-of-way through his brownstone quarry for Bradfield’s oil crew. That day little Lawrence Hinckley – [later] our artist in residence – happened to see the shooting. It scared him so badly that he fled to his father’s drugstore across the street, in the front door, out the back, and kept going. “Buster” Brown, too, a little older than Lawrence, saw the bleeding Henley come staggering down the street, bellowing with pain and with Bradfield still trying to gun him down. About that time Constable Owen Miller popped out of his Central Hotel and, as soon as the revolver was emptied, arrested Bradfield and took it away from him. Dr. Manning’ office was right there, upstairs, but Doc was out on a house call, so the bystanders loaded Henley into somebody’s spring wagon at the hitching rack, and “Buster” Brown earned his claim to fame because he got to hold one of Henley’s legs. The hand-written Criminal Docket No. 1 of the Fillmore Justice Court notes on July 2, 1914, that Bradfield appeared before Judge Merton Barnes on a charge of “assault with intent to commit murder.” Bradfield had raised $10,000 bail and hired a couple of young Ventura attorneys, Gardner and Orr, to defend him. The hearing had an amusing quirk, as told by the judge’s daughter, Barbara Barnes Jones. Dr. Osborn, called to testify concerning Henley’s wounds, was nettled by young Gardner’s cocky attitude and decided to show up that smart fellow, so laid it on him with answers in medical Latin. Gardner acted confused, and then suddenly shook the good doctor by asking a long question in the same technical Latin. Dr. Osborn hadn’t known that Gardner had spent a few years in medical school before taking up law. Judge Barnes had a hard time keeping his face straight. The Fillmore Herald reported that preliminary hearing in detail. The reporter, equally miffed by that smart young fellow from Ventura, commented a little acidly that “he ought to go far in his profession.” He did. Few in Ventura County have to be reminded that quick-witted Erle Stanley Gardner later became the internationally famous author of hundreds of best-selling novels based on legal doings. After Bradfield got out of jail, Constable Miller, who had tangled with Henley, too, gave him back his gun and said, as he told it around town, “Next time, do a better job.” |