|

The Fillmore Blacksmith

William Froehlich’s Blacksmithing, circa 1900, who operated the shop from the 1880s to the 1920s. Photos courtesy Fillmore Historical Museum. By Gazette Staff Writers — Wednesday, April 20th, 2022

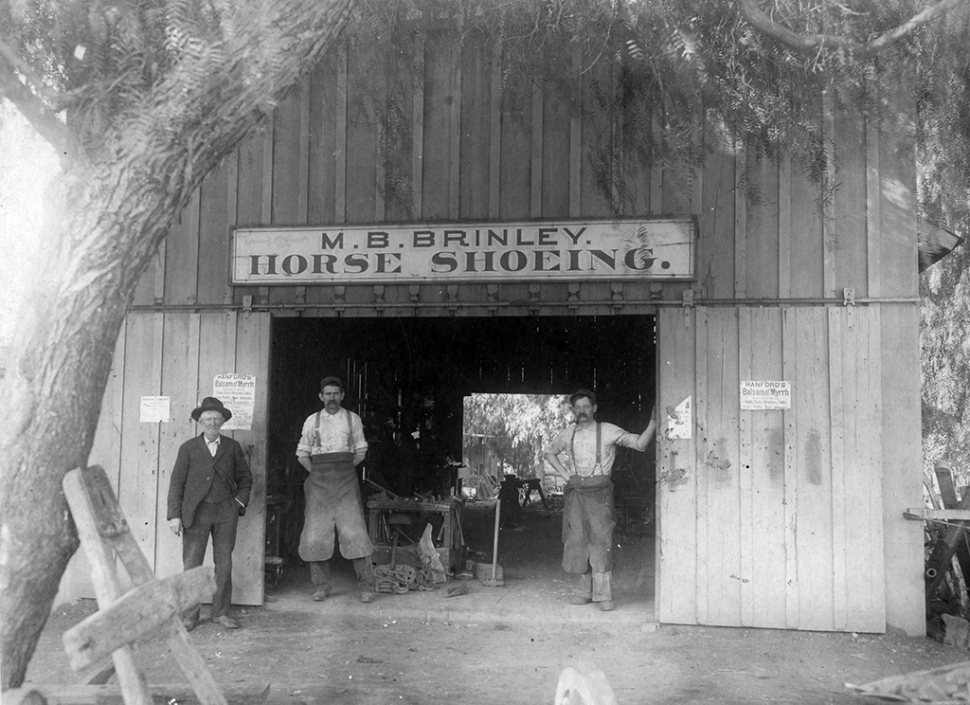

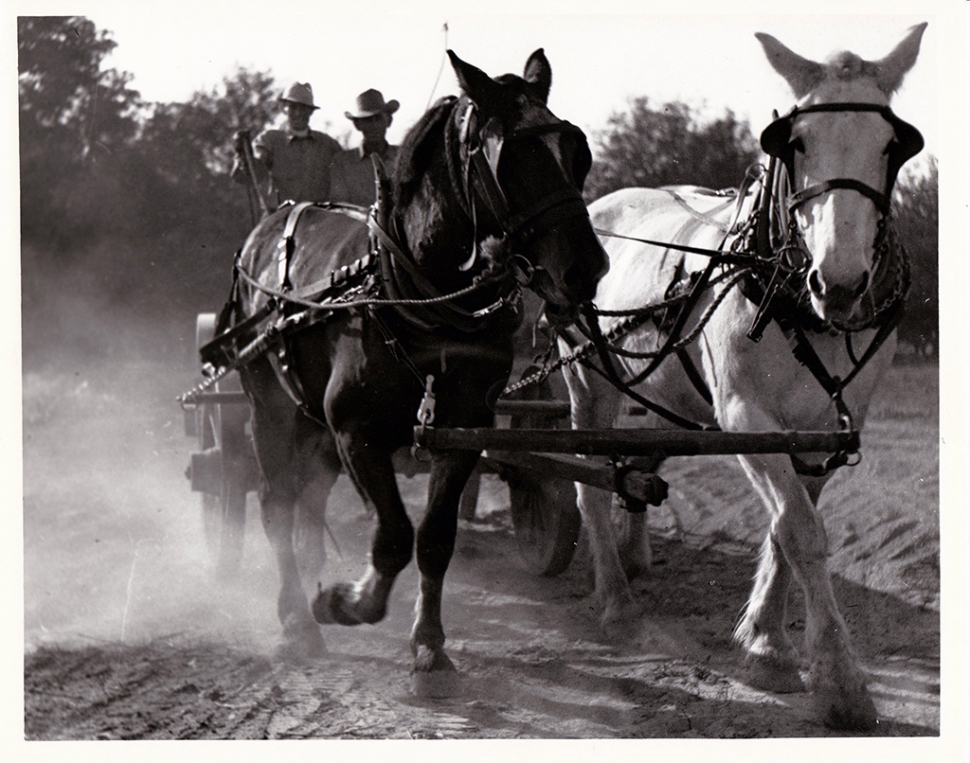

M. B. Brinley Horse Shoeing, circa 1910.  Horse team being watered outside Fillmore Stables circa 1900.  Working team of horses, Rancho Sespe, 1920s.  Inside of the Blacksmith shop, Rancho Sespe, date unknown.  Andy Godinez preparing horseshoe, Rancho Sespe, 1920s. Courtesy Fillmore Historical Museum Many historians would agree that obituaries are a great source for information. This is especially true of older obituaries which are often very detailed. An obituary on the front page of the January 25, 1946, Fillmore paper caught our attention for that very reason. The obituary was not for a person, but for a business, actually a particular type of business. The title read, “Fillmore’s Last Blacksmith Shop Dies In Peace of Natural Causes.” The article doesn’t say who was running the blacksmith prior to its passing and gives its location only as “on lower Central Avenue.” We do know from other sources that in the 1890s there were at least two blacksmiths, F. P. Brigham and Frank Cooper. These were no longer in business in 1914, but there was Hooper’s Blacksmith with the appropriate phone number, “Black 551”. The best documented blacksmith was William Froehlich (phone number Red 161) who for a time at least occupied the premises at 340 Central Avenue. He was in operation from the 1880s into the 1920s. By the time of the demise of the only blacksmith, the profession had changed a great deal. Originally, the blacksmith was an essential part of a community creating whatever might be needed from iron – from wheel rims to cooking pots to tools. With industrialization, mass production, and interchangeable parts, much of the job of the blacksmith disappeared. Before long the staple business of a blacksmith was horseshoeing. The profession became blended with that of a farrier. Many other blacksmiths branched out to work on the new phenomena, the motor car, morphing into auto mechanics. Blacksmiths as farriers were in demand in the Santa Clara Valley well into the 20th Century. At Rancho Sespe, horses worked alongside more modern tractors. Andy Godinez worked as the blacksmith/farrier at Rancho Sespe for many years and the Rancho had a well fitted out blacksmith shop. The obituary ends thusly: |