|

Fillmore Under Quarantine in 1918

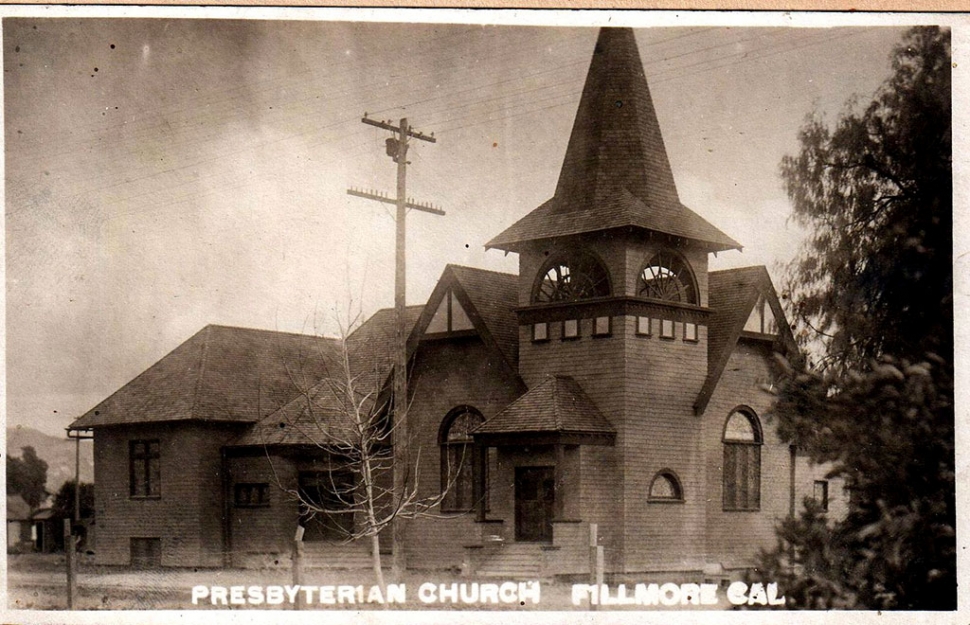

In October 1918, the first mention of the Spanish influenza appeared in a local newspaper. Pictured above is the Presbyterian Church circa 1910, which was converted into a temporary hospital in 1918 shortly after the announcement of the epidemic. Photos courtesy Fillmore Historical Museum. By Anonymous — Wednesday, January 27th, 2021

Vinnie Hinckley, daughter of Dr. J.P. Hinckley, who passed away at 15 years old due to the virus. Courtesy Fillmore Historical Museum The pandemic which swept the world from 1918 through at least 1920 did not skip over Fillmore. Inaccurately dubbed “Spanish” influenza, it was first identified at an Army camp in Kansas. The recruits shipped out to France and from there it spread. The “Spanish” appellation was derived from the fact that neutral Spain did not have the censorship controls that the Allied nations had and openly reported on the epidemic including the fact the Spanish king, Alfonso XIII, had contracted the disease. In the United States, it was believed that if the general public was aware of the situation it would hurt the war effort. The first mention of the epidemic appeared in the October 18, 1918, local paper. Because of the growing number of cases in the town, the school board debated closing the schools. After considerable discussion, it was decided to keep the schools open. Dr. W. R Manning, the city health officer, commented that there would be less danger of a serious epidemic if the children were kept in school than if the schools were closed and the youngsters allowed to run the streets. A week later, the tone in the paper was much different. The number of cases had exploded and there were deaths. Judge Merton Barnes, chairman of the Fillmore Red Cross, headed up the support effort aided by Mrs. Lawton and Mrs. Hadley as heads of the nursing team. At the suggestion of Hattie King, a temporary hospital was set up in the Presbyterian Church Sunday School at Sespe and Clay Streets. There the Red Cross volunteers aided the local Doctors Hinckley and Kerr as well as Dr. Soegaard from Piru and Dr. Mott from Santa Paula. Dr. Manning and his wife had contracted the virus so he was no longer able to attend to patients. Entire families were hit by the virus including the Harthorns, Fairbanks, Fosters, Froehlichs, Booths, and many others. A curfew was enacted, and public gatherings were banned. Pool halls and theaters were closed. A mountain lion hunt that had been scheduled was cancelled because the owners of the dogs were sick with influenza. By November 18, the epidemic seemed to have subsided, and the temporary hospital was closed. As a precaution schools remained closed. There was a sad report that the Reese family had lost 4 family members to influenza. Advice was given on the proper diet for victims. The situation continued to improve, and it was announced that the schools would reopen on November 25. It was decided that places of amusement should remain closed on Saturday evenings, when unusually large crowds congregate. The influenza of 1918, a strain of the H1N1-A virus, seemed to be particularly deadly to young adults, perhaps because it triggered a cytokine storm, which ravages the stronger immune system of young adults. This may explain why the next mention of the epidemic was on December 13, 1918 when a strict quarantine was announced. Dr. J. P. Hinckley, who lost his 15 year-old daughter, Vinnie, to the virus just a few weeks earlier, said he had twenty-five new cases, the majority of whom were high school students. Dr. Soegaard stated he had 19 patients, all high school students. It was decided that wherever the disease appeared a placard would be posted in a conspicuous place on the home, all cases had to be reported, and anyone residing in homes with the infections shall not be permitted to attend any public or private school or attend a public gathering. Churches were asked to cancel Christmas events and Mr. and Mrs. Richard Stephens cancelled their annual movie for the town’s children, although a toy giveaway would be held. |